Another idea of merit from the Victorian article, at least at first glance, is the use of the metaphor of Theseus and Hippolyta as a 'splendid frame'.

Normally we seperate the play into the world of the wood and the city - and that has merit too - but Hippolyta and Theseus, like all the human characters, move out of the city into the wood. Theseus and his soon-to-be bride have gone into the wood to do 'observance' prior to their marriage. They then intended 'to get in a bit of hunting'. The speration of town and country is not quite so rigid as is frequently made out.

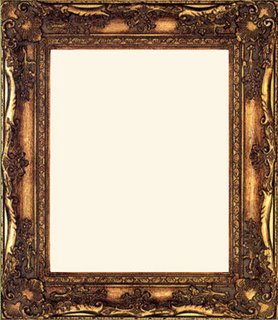

The idea of a frame, something which contains and limits (the idea here is of a rather ornate, Victorian picture frame), beautiful in itself, but which 'sets off' the contents, is interesting.

What is it that Theseus and Hippolyta have, are or represent that makes them suitable as a framework? One concept given to us is that of 'stately pomp': The frame is obviously covered in gold leaf.

Certainly the opening of the play would suggest such pomp - costumes in the Globe would be sumptuous for such figures as the hero and his 'Amazon', and the lovers and Egeus are aristocrates. Strict Elizabethan dress conventions would establish instantly for the audience exacly who and where these people were - courtiers in an urban, public place. Music would accompany the progress.

The After-the-wedding celebrations fit this pattern too - up to a point.

Conspicuous wealth on conspicuous show, something the Victorians understood.

However, this splendid frame gets a little disjointed - the mechanicals work their way into the wedding celebrations bringing with them a distincly tarnished patina and a danger of ugliness and ignorance. Almost a gargoyl on the cathedral wall (to crash quickly into another metaphor - the same way Shakespeare does by putting the mechanical's performance where he does).

And there are other twinges of doubt about the integrity of the frame - Hippolyta and Theseus don't quite seem to see eye-to-eye on a couple of issues: Her silence at the start of the play, after Egeus enters, 'speaks volumes' - so much so that Theseus has to ask, "What cheer my love?"

Their discussion of the role of imagination before the newly weds enter also smacks of disagreement, however civilized.

It is almost as if the frame also carries the themes of the contained picture, in a much more constrained way, but still complementary - not a neutral plain wood, but an active ornate, shallow carved but distinct piece of arabesque work?

So far I have concentrated on the constraining effect of the frame, but a frame also acts as a transition from the outside to the inside.

But more of that next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment