There is a tendency to portray Katherine as some sort of abused everywoman and Petruccio as a typical misogynist male. Indeed, this is the line taken in many classrooms and leads to a mistaken understanding both of the play and of Elizabethan society. Support for the stance can be found in the text – as long as you are selective in your reading - and is frequently supplemented by ‘common knowledge’ about the relationships between men and women in times past.

I would like to suggest that, far from being socially conservative in his views of male-female roles and promoting the status quo, Shakespeare is in fact questioning a centuries old acceptance of the inferior status of marriage (as opposed to virginity, celibacy and widowhood) and suggesting, in the words of Germaine Greer, the ‘complimentary couple’ as ‘the linchpin of the social structure’ (Greer, Shakespeare, A Short Introduction: pg 138).

Let me start with the abusive Katherine.

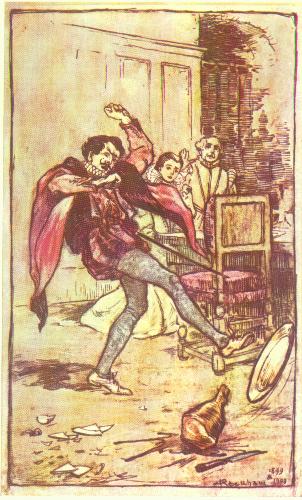

Few commentators dwell too long over the physical and emotional batterings Katherine doles out to all around her. She is clearly the most violent person in the play striking anyone she feels like: Three times she assaults men – Hortensio’s head is ‘broke’, Petruccio is slapped, and she beats Grumio: But her biggest abuse is reserved for her sister who she ties up, drags onto the stage and subjects to far worse treatment than anything she herself will suffer at the hands of Petruccio. It is worth noting that at no point (according to the script) does Petruccio strike Katherine.

If you add to this the ‘you don’t love me’; ‘you treat my sister better than me’; ‘you’re not a real man’ and other such jibes and comments which flow continuously from her mouth, she is not an attractive human being (although is great fun to watch on stage).

Presenting Katherine as ‘downtrodden victim’ is absurd. She is clearly out of control and her behaviour is causing misery to all around her. More importantly, in Elizabethan terms, she is also in danger of her soul – she is damaging not only her earthly marriage prospects, but her immortal ones too.

By the end of the play, Katherine has become a dignified, self-controlled rock; half of the foundation of what will become a strong family unit. Equally important is the fact she is now able to play a role in society (which includes lordship over the male servants) and is firmly on the path to a happy afterlife.

What brings on the metamorphosis is her pairing with a complementary force – Petruccio. The key word here is complementary – Petruccio balances Katherine, he is not the same and he is not ‘better’.

When he talks, early in the play, of ‘two raging fires’ burning themselves out, he admits his similarity to Katherine, with a difference – he is ‘pre-emptory’, she , ‘proud minded’. Together they will be in balance.

This is the point in the play at which the financial deal is done – again much misunderstood.

Both sides bring money – Petruccio, who has just inherited a considerable fortune, is sensibly seeking an equal amount: This will benefit both himself and his wife – and lay in a strong inheritance for any children. Marriage is all about family, it is an economic and social union – as much today as in Elizabethan days.

What people miss in this exchange is Petruccio’s leaving of everything to his ‘widow’ in the event of his early death: Katherine gets everything – she becomes an exceptionally wealthy woman. There is no need to bargain over this point – it is freely given. It shows Petruccio has complete faith in his wife-to-be’s sense and economic astuteness (hence the need for a female from an equal house). It also disproves the ‘goods and chattels’ view of the relationship regularly suggested – since when have goods and chattels inherited themselves?

Which brings me on to another frequently expressed view – Petruccio is only interested in the money. He certainly says such a thing when he is talking to Hortensio – but he uses an interesting expression to do so, he talks of finding a woman rich enough to be his wife, then he goes on to use the word wealth – “to wive it wealthily”.

The word wealth is suggestive of more than money – could it be that Petruccio is being deliberately ironic in his choice of word? Later in the play, when Katherine has been deprived of the expensive fashionable gown and hat, Petruccio says, “for ‘tis the mind that makes the body rich” and points out the jay and adder have earthly looking riches but inwardly are not better than other creatures.

Petruccio has seen Katherine’s potential – as an equal, not as an inferior. He has chosen her as a balance … and negotiated with her father for her hand.

And her father has given as much as he can of her – but he demands, before agreeing, that Katherine agree. He demands Petruccio win Katherine’s ‘love’.

We do not see the intervening days between the first encounter of Katherine and Petruccio and their wedding day – but there is ample opportunity for Katherine to stop the marriage – she doesn’t. She waits for Petruccio on the steps of the church – she would be asked in church if she accepts Petruccio, and she must have said, before God, she does.

All of this suggests, whatever public face she puts on it, Katherine has accepted Petruccio – it is a mutual not an enforced marriage.

Katherine’s last speech, rather than being an act of submission to oppression, is a recognition that the former firebrand Katherine was counter productive – there is always a stronger than you. It is a contract laying out the conditions needed for peace and prosperity, for right balance and mutual benefit.

But it is only half a contract – Petruccio is as bound by unspoken bonds which lay duties and commitments on him. He binds himself to her with a kiss – and physically they become one – not lord and servant, but a unity.

Shakespeare, in The Taming of the Shrew, is laying out, possibly for the first time on the English stage, a view of society where the mutual support of man and wife is the foundation of peace and contentment for society as a whole. It expresses not a view that women are subservient to men – but that only by mutual support can fulfilment be attained.

The battle of the sexes, shown at the start of the ‘Shrew’ play-within-a-play, is destructive and holds back both the individual and the community. Only by joining with the balancing power of a marriage partner of the right fit can life find a fuller, and more soul-fulfilling path.

Technorati Tags: Shakespeare, Taming of the Shrew Gender Relations

Does Petruccio, when he says he comes to 'wive it wealthily' mean this worldly wealth - or is he saying something else?

Does Petruccio, when he says he comes to 'wive it wealthily' mean this worldly wealth - or is he saying something else?

I cannot emphasis the last five words enough for an Elizabethan audience - Petruccio's 'taming' has saved Kate (and himself) from Hell's flames.

I cannot emphasis the last five words enough for an Elizabethan audience - Petruccio's 'taming' has saved Kate (and himself) from Hell's flames.

The induction does add to the play - if you think about it.

The induction does add to the play - if you think about it.

We have here the '

We have here the '