If there is any wisdom in the adage, ‘Out of Sight, Out of Mind,’ the Duke has a chance of his daughter falling in love with Thurio – but there isn’t; especially when he enlists Proteus as a go-between.

This Duke seems to know more than most – there is a look in his eye as he claims Proteus as a ‘friend’, and his parting, “I will pardon you,” almost has an all seeing quality to it. It is also Antony’s, ‘ ..Now let it work’, and Oberon’s sending of Puck out to solve the lover’s problems: Here is both care and mischief combined.

Suddenly we are in the woods – and the design makes a leap – this is not an identifiable wood – the trees are tubes of something – almost a dream world. If the earlier scenes have been Wodehouse, now we are straight into Gilbert and Sullivan, complete with lovable bandits. Surely one has the look of Robin Hood - in Lincoln Green? Another, more robust, an escaped character from Pirates of Penzance? Smiles and flashing teeth in tasteful, and clean, dishevelment.

Valentine (with Speed) wanders in, is captured and instantly impresses enough to be made ‘King’. This is the material of fable and romance – Don Quixote should be here …

Back in Milan Proteus sets about wooing Silvia ‘on behalf of’ Thurio – musicians to serenade included. As they set about tuning their instruments, for these are real musicians and will play live, as they have throughout the production, in creeps the disguised Julia with the host from her inn – who has brought ‘him’ to find the gentleman ‘he’ asked after.

Proteus sings – ‘Who is Silvia?’. He is not a great singer, his voice cracks a little – which makes an honesty of Julia’s lines about not liking the musician. In most productions the song is sung by a beautiful voice – it is the sort of stand alone song which is easy to take out of context – the BBC refused to follow that path and consequently made it a revealing element.

Proteus gets rid of Thurio and the musicians, and engages Silvia in conversation – she on the balcony, he below. He tries to persuade her of his love, she reminds him of his former love – who comments throughout. Another set piece – beautifully controlled. In the end Silvia, to get rid of Proteus, agrees to send a picture of herself in the morning, and Julia, wakes the snoring Host, and departs heavy of heart.

Enter Sir Eglamour with the daybreak. I wondered where Don Quixote was, and Eglamour, if not the romantic knight himself, is the spitting image. It is a bombasting, deep voiced, rounded sound and movements performance. Silvia has entrusted him with a plan to help her escape the city and follow Valentine. They will meet at Friar Patrick’s cell, where she is to go for confession (!).

Launce fills in time with his ungrateful dog speech – lest we forget how topsy turvy the world has become: And in case you haven’t got the point, in walks Proteus employing ‘Sebastian’ (martyr killed by shooting full of arrows – in this case, cupid’s) the name Julia has taken on, to go to Silvia and deliver the very ring he exchanged with her on departing Verona, as a gift for Silvia and a sign of his ‘love’.

Proteus departs, Julia philosophises, Silvia enters.

Julia attempts to deliver the ring, Silvia, recognising it, rejects it – and you notice the make-up. Sebastian has darker skin than Julia, having thrown away his veil, and then goes on to use the multilayered ‘boy acting girl acting boy’ who acted ‘a girl being betrayed by a man’ image. It is delightful. The peel of sound released from that bell tower will resound through all of Shakespeare’s latter works – it’s there in ‘All the World’s a Stage’, it’s obviously there in ‘Twelfth Night’, but also in ‘Othello’.

And you are back into the play.

Julia and Silvia part, Eglamour enters, Silvia re-enters and they go off together to the forest. There is a build up of pace – but not enough to make things hasty … there is still time for another quick exchange on love.

Thurio is in conversation with Proteus about the success of his suit – Proteus gives evasive answers but Julia, now transformed fully into a page boy, comments in asides mirroring Speed earlier on in the play – and just as before, the Duke enters. He asks after Sir Eglamour and his daughter – Friar Laurence met them in the woods and (obviously having learnt his lesson) reported their flight to Silvia’s father.

The hunt is on … into the woods we all go.

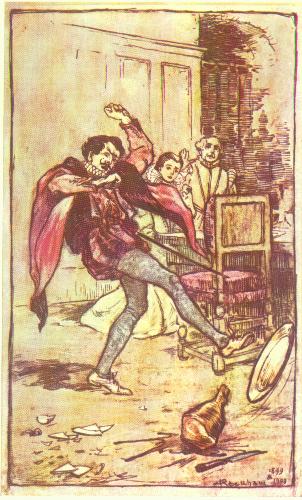

The production added the fight, flight and capture of Silvia in fine swashbuckling detail – and she’s taken off to the ‘Captain’ of the brigands.

Valentine, sighing, lamenting, and ‘doing penance’ in the woods hears approaching voices and hides. Proteus, having rescued Silvia, and accompanied by Julia, attempts to persuade Silvia, then force his love on her. Valentine interrupts – and soundly ‘tells him off’.

When reading the play, this scene causes consternation; watching it, it doesn’t.

Valentine is a prefect who’s caught a naughty fifth former cheating at cricket – it’s a game. He’s more concerned with honour and friendship than any sexually driven love. This is the threatened assault of Demetrius in the woods – just gone slightly too far.

When Proteus ‘confesses’ it is genuine – when he repents, it is true. No audience has time to ‘go deep’ at this point – things are happening too quickly.

For Valentine now to give Silvia to his friend is almost an expression of faith in Christian forgiveness – and the production made it seem just that.

Julia’s fainting brings us all back down to earth (again).

Suddenly everything unravels – the mistake over the rings and the revelation of Julia in a shower of golden hair; Valentine, seeing his true love next to the mirage of Silvia, returns to the fold of faithful lover; the Duke, captive in the script – but not seeming so in this production, (with Thurio, who quickly disowns Silvia) bestows his daughter on the now worthy Valentine.

And off everyone goes, to an explanation and a wedding, or two.

There was a sense of great satisfaction at this point. The darkness had been but the shadows cast by a full glorious summer sun.

The BBC’s policy of shooting in great chunks – a full scene at a time, worked well; the casting, superb; the underplaying of both Launce and the Duke giving more a feel of wholeness and lightness than of slapstick; the design never letting go of the literacy and genre of the piece.

A final note on the music – essentially English composers of the period, live and weaving melancholy dance tunes throughout – a great success in television where the usual practice of ‘sound track’ adds a mechanical aspect to what should be ‘live’.

Technorati Tags: Shakespeare, BBC, Two Gentlemen of Verona

We have here the '

We have here the '